June 1, 2022

French Toast

For three days I have had French toast for breakfast. It is the most delicious French toast I have ever tasted. Here, at Ardtara in County Antrim in Northern Ireland, they have opted to call it what the French call it, “pain perdu.” That means “lost bread” as the French came up with the idea to make use of yesterday’s stale baguette.

Maybe it tastes so good because it is. Maybe because of the name. Maybe because, as I sit here feverishly jotting down recollections of yesterday, I just might possibly be the happiest I have ever been.

I’ll admit that might color my judgment, but it is good French toast.

Seems to me that each of us is allotted so many days in our lifetime. Some good; some bad. Some pivotal, some routine. Some memorable; some we’d just as soon forget.

For those of us who have lived a good many days, we have the luxury of hindsight and perspective. If we are so inclined, we can reflect on and judge which days in our lives were our best. Some, such as the births of our children, come readily to mind. Some stand out because of an event or an accomplishment.

I suspect that many of the best days of our lives pass unnoticed, mistaken as routine, when in fact it was those days where we were at our best or the happiest. Halcyon days are awarded that distinction too late and only if sufficient time has passed by which to draw a comparison.

For many, the “best day of our lives” comes early. My guess is that most folks would point to a day in their youth, a carefree time before the weight of responsibility took its toll. It is, I think, rare that what might be the best day of our life occurs in the twilight of our years when our days grow shorter.

On Sunday, May 29, 2022, just shy of my 66th birthday, on the north coast of Ireland, I awoke to just such a day. A new day. A perfect day.

It all started with the French toast.

Nine O’Clock: The Staff

We sit down to breakfast. Cathy her coffee, me my tea. The milk and sugar are a blue willow pattern, much the same as Cathy’s Gram’s. We take this as a sign.

I ask our waitress, Elena, to take our picture. She is almost giddy with excitement. News has spread quickly through the small staff at Ardtara of the older American couple eloping.

The manager Sean, a wiry fastidious man with a wry smile and a mischievous laugh . . the kind of man who will, after you’ve asked for an iron and an ironing board, pinch your forearm and whisper in a conspiratorial way “no problem, no problem d’at all” as if he were agreeing to place a bet with a bookie . . . has gone into the garden to cut flowers himself, unsatisfied that the florist who provided a bouquet upon our arrival had done an adequate job. He assures us, with a wink and a nod, he will put a bottle of champagne on ice for when we “come home” tonight.

Nicola, the middle-aged woman pushing the vacuum over the old rug in the entry of the old manor house, quickly turns it off and, beaming, steps aside to let us pass, as if we were movie stars or royalty.

A young woman, sitting alone at a long banquet table, struggling to contain her squirming toddler who is crawling from her shoulders to atop her head as if she were a jungle gym, strikes up a conversation. She is waiting for the rest of her family to join her. He presses his face to hers; I comment that he gives new meaning to “Facetime”.

She apologizes for her son’s shyness when Cathy reaches out to greet him and he recoils. She shares that he loves chocolate and has somehow been convinced that it can be found beneath tables. I tell him this is true, that that is where I often look. His mom laughs, but good naturedly furrows her brow just a bit to suggest I am not helping her efforts to corral him.

When we tell her of the day’s plans, she is thrilled and says, “Oh, that’s lovely.” This is a reaction we get everywhere we go. People seem to take it as a sign that life might return to normal, and happiness might still be found.

Ten O’Clock: The Walk

Ardtara is the old home of Henry Jackson Clark, his wife Alice, their four sons and two daughters. It was built in 1896 for “Old Harry” and his family to escape the thunderous noise of the Beetling machines in the linen mills the family owned in Upperlands.

The grounds consist of expansive lawns, a path that meanders around the perimeter of the property where, with each bend on the trail, you discover a statue or a gazebo or a small bridge leading to an island in a pond. Sean points out that two redwood trees were shipped from California in 1907 at the price of a king’s ransom.

Cathy and I set out to stretch our legs. The path floor is made of wood mulch compressed over time and feels remarkably the same as the pedestrian conveyor walks in the airport in Dublin.

Half Past Ten: The Dress

We return to our room, and I sneak a glimpse of Cathy’s dress hanging on the door. Before I shuffle off to the parlor for a cup of tea, catch up on my writing, and allow her to “beautify”, I tease her that the flowers from Tracy at Willow and Twine will complement the color of her dress, “at least as I imagine it.”

With that, I am banished to the parlor. Sean, Elena and Nicola take turns looking in on me, asking if there is anything they might get, perhaps “a wee more tea”, and later suggesting “shouldn’t ye be getting ready yourself?” I reassure them we are on schedule, and it won’t take long.

Unbeknownst to me, poor Cathy, without a bridesmaid or her mum to help her, without so much as a magnifying mirror to help her see and relying on a hair dryer that seems powered by the same stream than must have kept the Clark family’s linen mill running, manages entirely on her own to get ready.

When I return to our room, I am given two tasks. The first is to button up the last of many buttons on the back of her dress. I nail it. The second is to unfasten the tiny clasp on her Diabetic Medic-Alert bracelet. After I struggle for five minutes, fumbling with shaky fingers, we agree—but later forget– to try again before the ceremony. Cathy will wear it when we exchange vows.

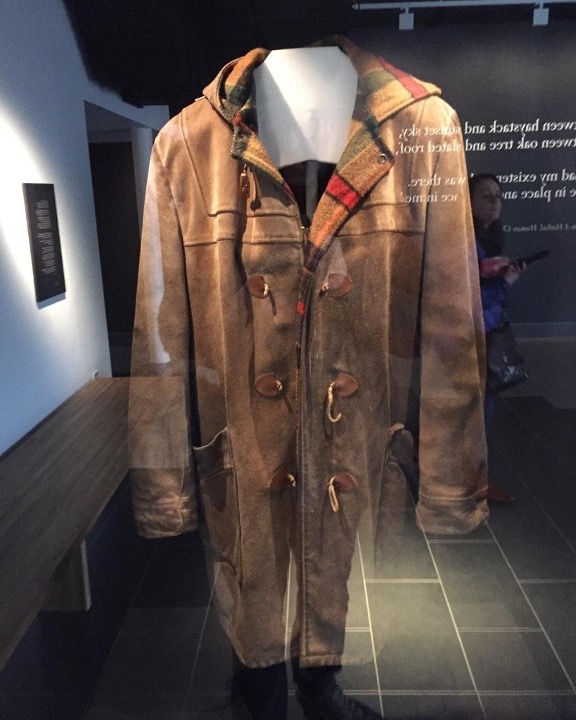

Did I mention the dress? No? Well . . . That lies beyond my poor words to describe. Imagine something so beautiful–settling like a sigh on soft shoulders, silk the color of linen beneath Irish lace, embroidered flowers trailing to the ground—a dress so beautiful that it can only have been made by the faeries.

Half Past Two: The Roundabouts

Our officiant Sam Hannah, a shy and soft-spoken man with white hair and dark glasses, explained to us when we first met, that the roundabouts in Coleraine are particularly treacherous. This has Cathy on edge. We allow for extra time to drive north to the Antrim Coast.

I have driven . . . oh . . . I don’t know . . . maybe fifty yards on this trip. That is when I bring the car up from the car park to the manor house. That journey is not going well. First, I struggle for minutes trying to work the electronic seat controls of the damn Mercedes, only to discover the means by which to move the seat up or back is an old school mechanical spring-loaded adjustment lever hidden well below the seat. As minutes pass and Cathy waits above, I grow more and more nervous.

Finally, I climb in with my knees up to my chin, race up the driveway, run in, follow Cathy out to the car, a bouquet in one hand, our day packs in the other. We plop into our seats. Cathy pushes the button to start the engine.

Nothing happens. We look at each other. She tries again. Nothing happens.

Panic is well underway when it dawns on me that I must have left the high-tech electronic key, without which the car will not start, in the room. I grab the room key, race back into the house, staff asking if they might help, fumble with the old-fashioned room key, retrieve the wizzy-wig Mercedes key and race back out.

We’re off!

“Hero status” has been bestowed on me once or twice on this trip, but never has it been better timed nor better received than when, applying my mad navigator skills, I route Cathy thru Ballymoney, bypassing Coleraine and it’s diabolical multi layered roundabouts.

I am her hero once again.

Four O’Clock: Farmer Sean

We are to meet Sam, the photographer Kelly, and the farmer Sean at a small cottage near the entrance to Dunluce Castle. Kelly has told us look for a yellow door. Sam has told us look for a red door. This has me worried. I fear that, even if we find the right door, there will be a sea of tourists and little or no place to park.

We pull in. It is a yellow door. Cathy performs a miracle parallel park a bit down the road which, to have adequate room, requires that she snug the car up against a tall grass embankment on my side. The woman is amazing. In a wedding dress with high heels, she can parallel park on the left from the right side of the car.

She steps out. I struggle to crawl over the console, get my leg caught, and crawl out hands on the pavement, tie dragging, mortified as the passing tourists chuckle at the sight.

It is windy. I suggest Cathy wait in the back seat and promise to be right back. I walk up the hill to find a tall lean man with gray hair, his hands thrust deep into the pockets of his green working coat, standing outside the white cottage with the yellow door. I ask, “Sean?”. He asks “Robert?”

We step inside. He and his wife greet me. They are soon joined by Sam and his wife. Kelly, the photographer—a kind young lady, dressed in a parka, with a ski cap pulled down over her ears, two cameras hanging from her neck, arrives.

Sean and his wife, and Sam and his, have been married for many years. I ask Sam, an almost painfully shy man, “How long?” His wife rolls her eyes when he does the computation in his head.

We chat for a few minutes, when Sam’s wife asks, “Have ye forgot something, Robert?” I reach for the rings in my coat pocket, mortified that I have lost them, and reply, “No, I don’t think so.” Sean says, “yer bride Robert, yer bride.”

I say I will go fetch her. Sean, a prankster at heart, says “no, let me do it.” Out the door he flies as I say “she is sitting down the road in the back seat of a Mercedes. Sean shouts back over the wind, “I’ll find her” and takes off.

Cathy is sitting in the back of the car wondering where I am when a strange man jumps into the front seat behind the wheel without looking back. He says, “hi” and tells Cathy “From the back I’m the spitting image of your husband to be.” Cathy, suspecting that it is Sean the farmer, replies “close, but not Rob.”

They return to the warmth of the cottage where Sean steps into the kitchen, return with two brandy sniffers and a bottle of Scotch. He pours two glasses to bolster us against the wind. We rib Sean that it is Scotch, not Irish Whiskey.

The ladies ooo and ahhhh over Cathy’s dress. Sam’wife—a short, solid, no nonsense woman with short gray hair– teases him, “How come, ye’ve never been so romantic?” Sam shrugs and looks to Sean for help. The small cottage is filled with laughter. Sean hands Cathy and me a 20 euro note and makes us promise to buy two proper glasses of Irish Whiskey at our next pub as a wedding gift from him.

Half Past Four: “Here Comes the Bride”

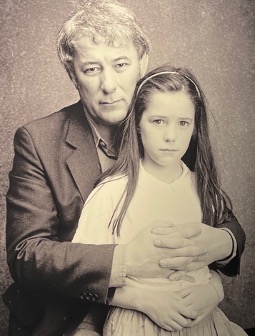

Our ceremony will take place on a bluff on Sean’s property. You can see it in the distance in this picture. Sean’s family has owned the property since 1957.

Sean insists that Cathy remain behind as he drives me, Sam and Sam’s wife, and Kelly in his Volkswagen pick-up truck out to the bluff. I tease him, “You won’t lose my wife, will you?” He teases me back that “Not to worry Robert; if I do, it won’t be more than an hour or two.”

He drives back up the hill to fetch Cathy.

Most grooms stand by the minister as they watch their bride walk down the aisle. Sean had another entrance planned. As Sam and I stand, backs straight, our hands solemnly folded in front, Cathy makes her slow entrance in the front seat of a pick-up truck alongside Sean. What an entrance! She is 500 yards away and already I start to well up

The ceremony is brief. Sam, with a soft Irish lilt, has done a masterful job of preparing just the right words, using the “stories” he asked us each to write, but not share with one another, and weaving those stories of how we came to fall in love with his own comments about marriage, poetry we selected, and just the right amount of humor. He has us both crying and laughing.

We exchange rings, say our “I do’s”. Kelly floats quietly about clicking photographs. She is a pro and does not intrude. I am scarcely aware that she is there.

Sam’s’s wife stands back at a distance. She strikes me as not the kind to cry, but she does. When Sam asks her to hand him the book in which we have written our vows, she is startled, having been lost in thought, and scrambles through the heavy grass to hand it to Sam.

I have to stop here. Although I can recount our vows, I cannot describe the look on Cathy’s face. I won’t even try. That will have to await Kelly’s photographs.

Sam steps away some distance leaving Cathy and I alone to hear one another. We have typed our vows in large “easy reader” font in a small green journal with a Celtic knot on the cover, knowing that without our glasses and without large type, we will be unable to make them out.

Rob’s Vows to Cathy

How can it be that every night I fall asleep certain that I cannot love you more and awake the next day certain that I do?

How can it be that two people who have lived a lifetime apart can know each other’s thoughts as if they had spent every moment of every day together?

How can it be that, in all this beauty–the sea, the land, the sky—they all fall out of focus and the one thing that takes my breath away is the sight of you.

Because of you, Cathy, I no longer believe life is random. It’s more than fate. More than destiny. It’s more than big G God, souls or faith. Those words . . . any words . . . are leaden. They fall short, too heavy to ride the wind.

Meeting and falling in love with you Cathy have taught me there is an elegance to this universe that I can understand only if I accept impossibilities and I can glimpse only if I pause long enough to look at simplicities.

I see it in

- The way you fall asleep with your chin back and your glasses tilted forward on your nose as if you were reading your dreams.

- The way you position cartons and bottles and jars in the fridge so the labels face out;

- The way you look for your glasses, not knowing a pair, sometimes two pairs, are perched on your head.

- The fact that, right now, only you and I would wonder “Is it proper to say ‘two pairs of glasses or two pair of glasses’”;

- The way in which you talk to dogs and babies as if they were the same;

- The way your face lights up in the glow of your phone in a dark room and I know it is a video of Avery or Olive;

- The way you look at photographs of Nick and get lost in memories

- The way you hold your mother’s arm as she descends the steps;

- The way your eyes mist up at the memory of your dad;

But if there is a god or a force or a cosmic answer in this world, I can hear it every day in the sound of your laughter. Your laughter and your smile are all that I want and all that I might ever hope for and. . . for me . . . the only necessary answer to the question “why.”

And so I make this promise, Cathy

I shall shelter you against the wind,

And hold you close beneath the stars,

Stand watch against the dark of night,

And be there in the mourn.

I shall set my teacup softly down

Not to wake you ere you stir,

I shall kiss your forehead and your hand

And hug you tight against my heart.

I shall get down on these aching knees,

To build dollhouses for your girls,

Your family is my family now,

Your children now my world,

And each night that we climb the stairs,

My steps not far behind,

I shall whisper to my weary self,

Thank god, your love is mine.

Cathy’s Vows to Rob

We are finally back in Ireland, but this time together. It feels so right to be at this place, at this time, joining our lives together and creating a new loving family.

I feel the presence of Gram and all of our loved ones that have passed away smiling down on us right now! They, along with our family and friends at home, have us in their hearts as we pledge our love to one another.

I could never have guessed that fate and luck would join together, and I would find the love of my life at Trader Joe’s. We followed a crooked road to find each other, but I truly believe that our story was written in the stars a long time ago.

Rob, you are simply the best man I know. I have such respect for you. You bring joy and laughter into my life and a love that I have not known before. You are full of kindness and intellect and humor. You challenge me, you encourage me . . . you comfort and protect me.

And, in return, I promise to stand by you through thick and thin and happy and sad. To be your refuge when the world seems dark and to be your confidant to safely share your thoughts. I promise to be your equal partner . . . sometimes to follow the course you set and sometimes to lead when you tire . . . but always by your side in this adventure together. I promise to never stop embracing this magic love we have found.

And this final promise is the easiest . . . I promise to love you for ever and ever. Of course

Rings exchanged, vows exchanged, Sam leads us through the handfasting ceremony. Holding one another’s hands, he weaves the beautiful braid Cathy, Jackson, Avery, Finn, Grady, Olive and Rhyse have made, around each of our wrists. We officially “Tie the Knot” in the Irish way.

Sam concludes with the Irish Blessing:

May the road rise up to meet you,

May the wind be always at your back,

May the sunshine be warm upon your face,

And rains fall soft upon your fields,

And, until we meet again,

May God hold you in the hollow of his hand.

We kiss . . . and laugh.

Five O’Clock: Photo Ops

We are crying. Kelly agrees to take a couple of photos with our cell phones. We insist that Sam’s wife join us in a photograph. She refuses, embarrassed at her appearance, but we eventually prevail.

Sean drives us all back to the cottage. We say our goodbyes.

Kelly has selected three sites for photographs, each fifteen minutes down the road from one another. She leads in her car; we follow.

Kelly is sweetheart of a girl. She leads us through some steep and sketchy terrain, always solicitous, helping Cathy in her struggle, a hopeless struggle against the wind, to keep her hair off her face, reminding us that we don’t have to chance a shot near the edge of a cliff or a walk down a steep slippery slope.

Cathy resists her entreaties to swap more stable shoes, preferring instead to scamper over rocks and pick her way down boggy slopes in high heels. As Cathy drives to the next stop, she empties sand from her shoes.

First, we stop at Dunseverick, a beautiful sloping ravine to a hidden cove where the remains of a castle are perched on a bluff above.

Next it’s on to Ballentoy Harbor.

Finally, we stop at the Dark Hedges, a haunting tree lined road. Kelly has carefully timed our arrival for just before nightfall so as to avoid the crowds of Game of Thrown fans who come in busses dressed in costume. It is bitterly cold now and the trees a long walk away. Kelly is bundled in her parka; Cathy has nothing more than her shawl.

Half Past Eight: “The Coolest Grandparents Ever”

We walk back to the cars and say our good-byes to Kelly. She asks, “Ye two are grandparents, right?” We say “yes.” She comments that young couples have declined to go where we trapsed. As she opens the door to her car, she says, “You two are the coolest grandparents ever.”

It is late. The weather which had held throughout the day is beginning to turn wet and gray. Cathy is freezing. My climate control skills are not much better than my navigating skills, but I manage to crank up the heat in the Mercedes.

We meander through the countryside and find a roadside Italian restaurant Kelly has recommended. It is not elegant. Not one tourists frequent. The folks are local families, casually dressed, familiar to one another, out for a Sunday dinner.

As we go inside, Cathy in her dress, me in my suit and tie and boutonniere, a buzz spreads through the restaurant. A young waitress with a kind smile approaches. The place is set to close at nine. Everyone is finishing their dessert. We ask if we might sneak in a bite before they close. She replies, “Of course, not a bother, tat all.”

We each order lasagna which arrives piping hot and delicious, but a serving so large that one could feed a family of four. Between us, Cathy and I have enough food to feed an army. We stuff ourselves so as not to appear rude, then ask for a box. The waitress returns with the box and two small bottles of champagne she has lifted from the back, clearly without getting approval.

I excuse myself to the bathroom. The moment I do, the waitress is joined by the other waitresses and girls on the staff, all crowded around Cathy, gushing over her dress, peppering her with compliments and questions. As each staff member rushes over, a new round of “Oh, that’s just so romantic” starts up again.

Eleven O’Clock: Home Again

We drive “home” to find wink and a nod Sean has chilled the champagne and arranged our flowers. We add the two small bottles of champagne from the restaurant to Sean’s whiskey money, Sam’s carefully prepared transcript of the ceremony, the other Sean’s newly cut flowers from the Ardtara garden, and our handfasting braid. So many well wishes of so many kind strangers.

We fall asleep without so much as a sip of champagne. It has been a picture-perfect day.

I think I’ll have the French Toast tomorrow.