Wednesday,

October 29, 2014

Santa Rosa, CA

As was the custom in the fifties when my brother, sister and I were born, my parents drew on family heritage to name their children. My brother, the oldest, was predestined long before conceived to become John Calvin Jackson, IV. That’s“the fourth”,with a comma in front of it. (Not everyone gets a “comma.”)

John’s son is “,V” and his grandson is “ ,VI.” Who knows what number he might have drawn had it not been for Rossanah Murphy–a pistol of a pregnant Catholic Irish lass who back in 1828 threw down her apron, said “Jesus, Joseph and Mary,” and, foregoing the first choice so as not to piss off the Presbyterians, and the last choice so as not to piss off . . . well . . . more Presbyterians, passed on yet another John Calvin and opted for the second choice , naming her son Joseph. I would have liked to have known Rossanah. She must have been a spirited woman to buck a bunch of humorless John Knox disciples stuck in their Protestant ways.

My sister Linda, bless her heart, was given the middle name Louise. I’m not certain, but I believe this was in deference to an aunt in East St. Louis, my only memories of whom are that she played Beethoven with such lightning like fingers that she could pull the Chesterfield King that seemed to perpetually dangle from the side of her mouth, tap the ashes into one of those beanbag ash trays on the side of the piano, and return her fingers to the keyboard without missing a measure. The name Louise was, in its day, a regal and popular name (in 1910, one in ten American girls was born Louise), but as with so many names, it fell out of favor, passed from sight, and like the names John, Linda, and Robert became “old fashioned.”

My mom used to remind me when I was a child, “Rob, don’t ever make fun of someone’s name or the way they look; they can’t help what God gave them when they were born.”

I don’t know about God’s participation, but Mom was right: we are born with the name our parents chose. Sometimes with rhyme, sometimes with reason, often with neither. Sometimes a name is a source of comfort. Sometimes a source of pride. Sometimes an inspiration. Other times an embarrassment, a mystery, or a burden

The dirty little secret that only parents know—and we’re sworn by some unspoken covenant amongst ourselves to never share with our children– is that we really don’t know what the hell we’re doing. We’re rookies. There were no minor leagues in which to practice. No spring training. All of the sudden we’re thrown in the “bigs” thinking “I’m not supposed to be here; I shouldn’t even be in right field.”

And the very first job we are given—our very first assignment– is to give this short story fresh out of the womb, not just a working title, but one suitable for framing on a college diploma, having no idea what the hell the book is going to be about. Think about it. It’s the name with which she will be scolded in second grade. It’s the name by which he will be asked to step out of the car by the officer when making out with his girlfriend in high school. It’s the name by which he’ll swear to take her and protect her in sickness and in health, and the name that will eventually end up in the local paper’s “Tribute Section.” (Apparently, someone decided “Tributes” with color glossies of the dearly departed sell better than the old black and white, copy only, “Obits.” Newspapers, these days: it’s all about visuals and revenue.)

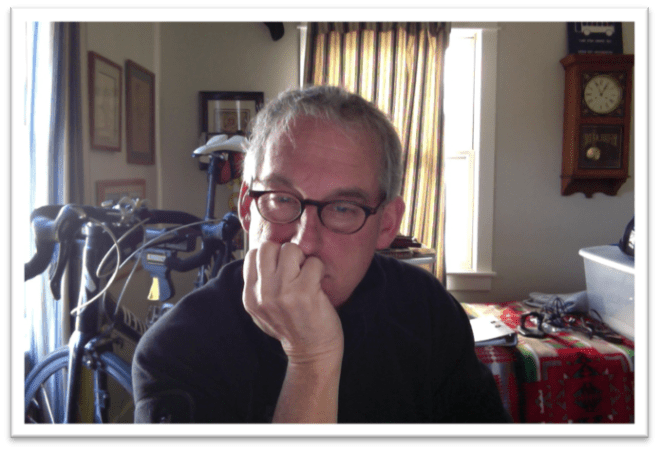

Anyway back to the point. My name is Robert Lear Jackson. I was named after this handsome young man who was my mother’s brother. We never met. He died “Somewhere in Luxemburg” on October 22, 1944. Nobody knows where precisely.

Uncle Robert

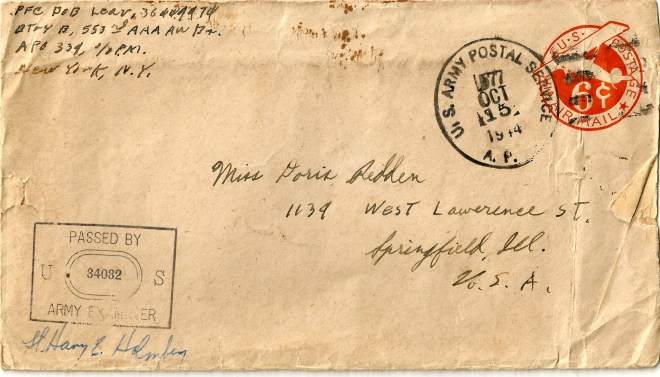

This is a letter he wrote to his Aunt Doris and grandmother (“Bawma”), ten days before he died

“Somewhere in Luxemburg”

Love, Bob

October 12, 1944

Somewhere in Luxemburg

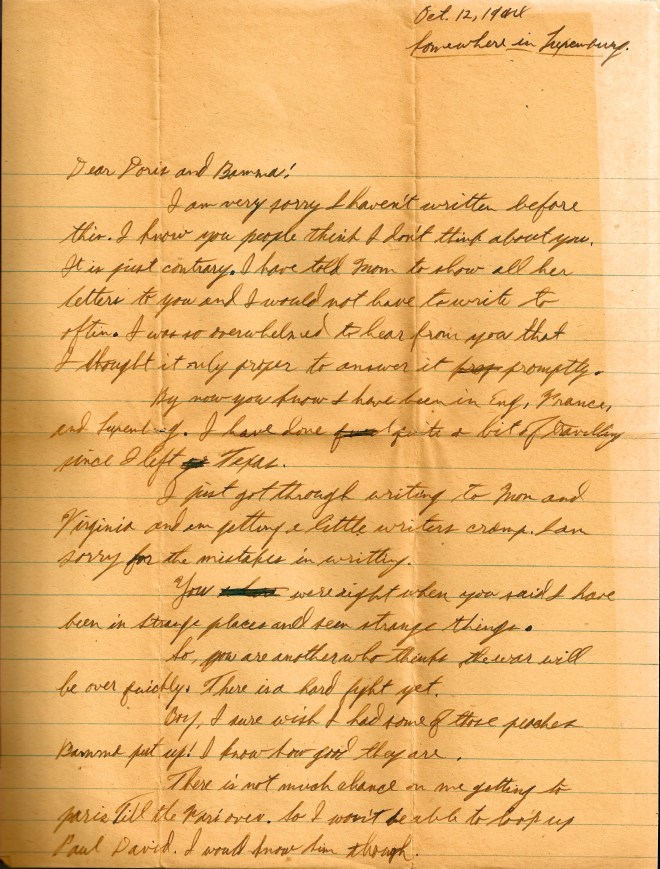

Dear Doris and Bawma,

I am very sorry I haven’t written before this. I know you people think I don’t think about you. It is just the contrary. I have told Mom to show all her letters to you and I would not have to write too often. I was so overwhelmed to hear from you that I thought it only proper to answer it promptly.

By now you know that I have been in England, France and Luxemburg. I have done quite a lot of traveling since I left Texas. I just got through writing to Mom and Virginia and am getting a little writer’s cramp. I am sorry for the mistakes in writing. You were right when you said I have been in strange places and seen strange things.

So, you are another who thinks it will be over quickly. There is a hard fight yet.

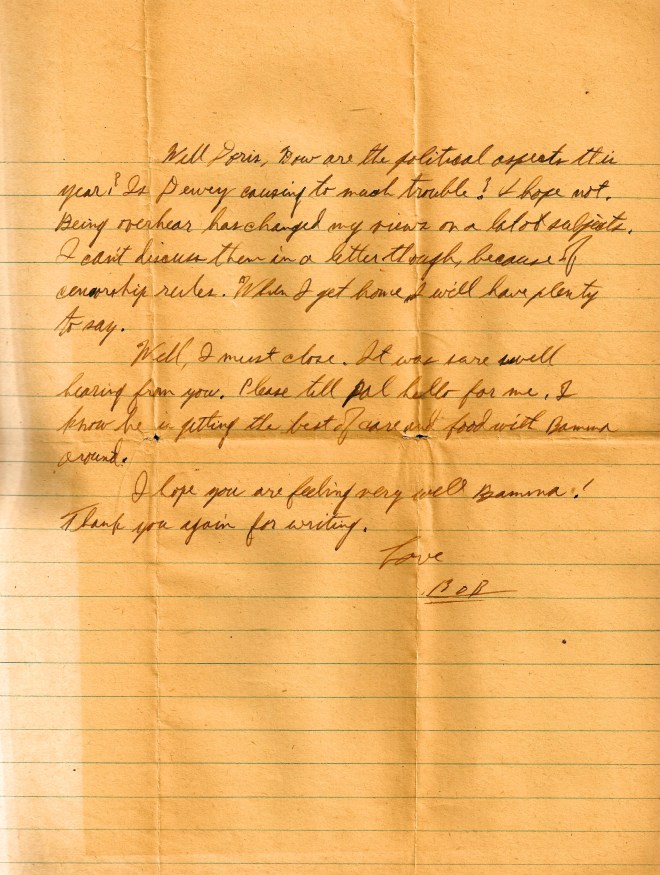

Boy, I sure wish I had some of those peaches Bawma put up. I know how good they are. There is not much chance of me getting to Paris until the war is over. So I won’t be able to look up Paul David. I would know him though. Well Doris, how are the political aspects this year? Is Dewey causing too much trouble? I hope not. Being over here has changed my views on a lot of subjects. I can’t discuss them in a letter though, because of censorship rules. When I get home, I will have plenty to say.

Well, I must close. It was sure swell hearing from you. Please tell Pal (his dog) “hello” for me. I know he is getting the best of care and food with Bawma around. I hope you are feeling very well Bawma. Thank you again for writing.

Love,

Bob

I’m going to find “Somewhere in Luxemburg” or at least get close. I’m not entirely certain where, and to be honest, I’m not entirely certain why. It is not important that I find the exact place where my Uncle perished. I’m not expecting answers. Hell, I’m not even sure what the right questions are.

I’m not doing this in a maudlin or morbid way. I intend to have a good time, see the Paris Uncle Robert never got a chance to see, and pay my respects to him and others who gave so much at such a tender age.

Names are important. They serve to foreshadow our lives, even when cut short. They challenge us to learn, to travel, and to step outside the comfort of our home to meet the hopes and expectations of our parents, as proper . . . or misplaced . . . as they may sometimes be. And if we are fortunate to live a long life, and respond to the challenges our names summon us to meet, perhaps one day our own name may encourage and challenge our children and their children and all the Roman Numerals that might follow to travel to places, both near and far, they might otherwise have never found the courage to explore.