June 2, 2022

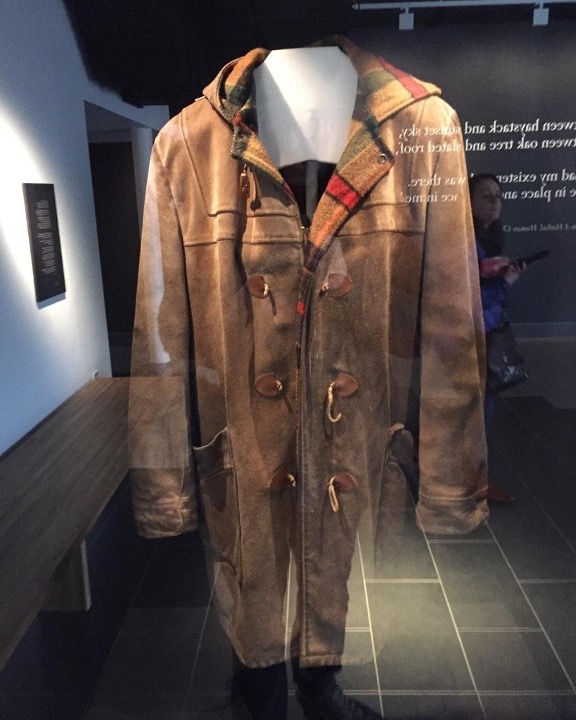

Seamus Heaney wore this coat. Most every day. It fit him.

Seamus Heaney, with whom I am only beginning to become familiar, was a Nobel Prize winning poet who grew up in Ulster just a few minutes down the road from Ardtara. He died in 2013 at the age of 73 and is the most celebrated modern writer, and perhaps the most revered man in all of Ireland.

A beautiful museum lies in Bellaghy, a small village northeast of Lough Beg, which chronicles his life and work and is perhaps, for a student of words, hallow ground. Exhibits show his family, and with each photograph, one can listen to him read from his own work. If you have a chance, Google a Charlie Rose interview with Heaney; it is important to hear his voice.

When Heaney was a boy, it was the custom that a boy follow in his “da’s” work. Heaney’s father, Patrick Heaney, worked in the fields and traded in cattle. His mother was Margaret Heaney. The two so loved their son, and knowing that his love and gift was writing, scrimped and saved to send him to St. Columb’s College in Derry.

As he left, they gifted him a Conway Stewart pen, a fine—very expensive—writing instrument. He would write poetry with it his entire life.

Perhaps Heaney is so loved by the Irish people because he so loved his own family. He wrote of them often.

Of His Aunt Mary

the reddening stove

sent its plaque of heat

against her where she stood

in a floury apron

by the window

Of His Father

I stumbled in his hobnailed wake,

Fell sometimes on the polished sod,

Sometimes he rode me on his back

Dipping and rising to his plod.

I wanted to grow up and plough,

To close one eye, stiffen my arm

All I ever did was follow

In his broad shadow around the farm.

I was a nuisance, tripping, falling

Yapping always

But today it is my father who keeps stumbling

Behind me, and will not go away.

Of His Mother

When all the others were away at Mass.

I was hers as we peeled potatoes.

They broke the silence, let fall one by one

Like solder weeping off the soldering iron:

Cold comforts set between us, things to share

Gleaming in a bucket of water

And again let fall. Little pleasant splashes

From each other’s work would bring us to our

Senses.

So while the parish priest at her bedside

Went hammer and tongs at the prayers for the dying

And some were responding and some crying

I remember her head bent toward my head,

Her breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives—

Never closer the whole rest of our lives.

Of His Wife Mary

Masons, when they start upon a building

Are careful to test out the scaffolding;

Make sure that planks won’t slip at busy points

Secure all ladders, tighten bolted joints.

And yet all this comes down when the job is done,

Showing off walls of sure and solid stone

So, if my dear, there sometimes seem to be

Old bridges breaking between you and me,

Never fear. We may let the scaffolds fall,

Confident that we have built our wall.

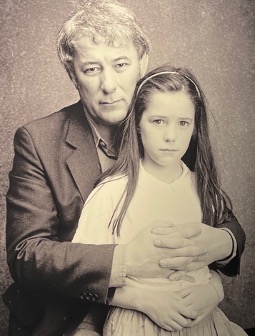

Of His Daughter

Aren’t poems like your toys, Daddy?

Catherine said.

And didn’t you and mommy make me

And God made the thread?

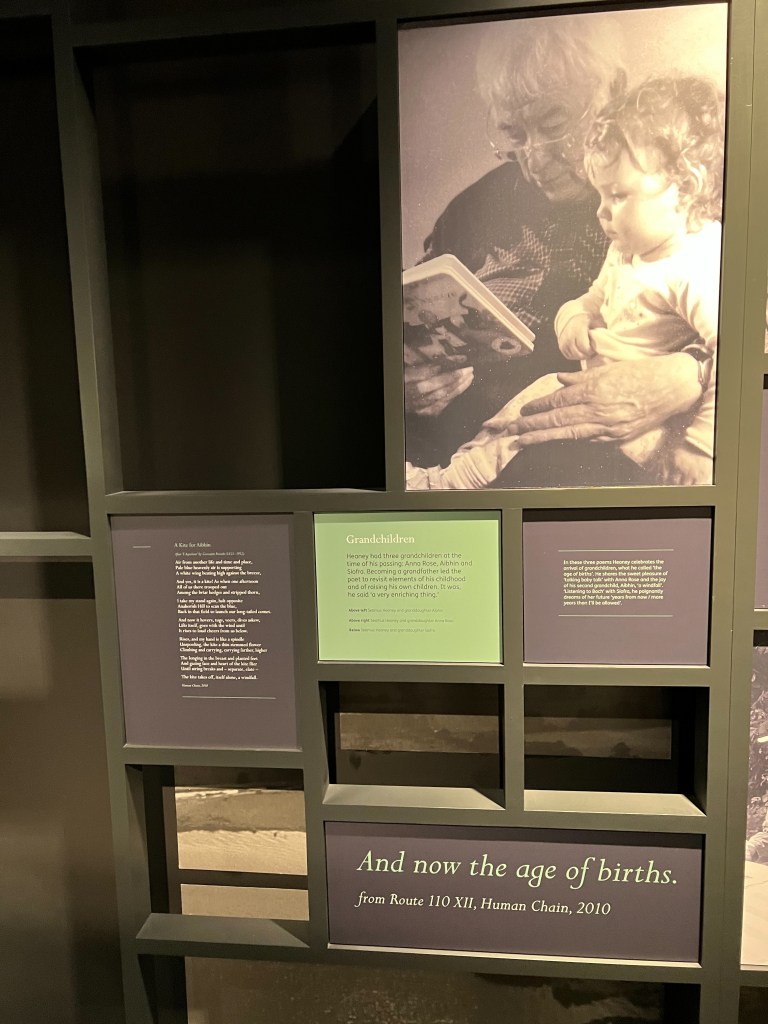

But it was his love of his grandchildren that I think most resonates with Cathy and me as we walk this museum. Referring to this time in life —when too often we see and fear death—he wrote, “And now the age of births.”

Of his granddaughter Siofra, he wrote this

Energy, balance, outbreak

Listening to Bach

I saw you years from now

(More years than I’ll be allowed)

Your toddler wobbles gone

A sure and grown woman.

Your bare foot on the floor

Keeps me in step, the power

I first felt come up through

Our cement floor long ago

Palps your sole and heel

And earths you here for real.

An oratorio

Would be just the thing for you:

Energy, balance, outbreak

At play for their own sake.

But for now we foot it lightly

In time, and silently.

Just moments before he died, Seamus Heaney–son of Patrick and Margaret Heaney, “Da” to Michael, Christopher and Catherine, “Daddo” to Aibhin and Siofra—sent a text message to his wife Marie, in his beloved Latin. It read, “Noli timere”— “Don’t be afraid.

This trip has been about family. It’s about Gram. The Rooneys. The Jacksons.

But our family tree is so much more than those two branches. It’s about the Perrys, the Lears, the Beckers, the Bachmans, the Casebiers, the Wallaces, the Sparkes. The best thing about a family tree is that it is a tree. And a tree grows. It keeps growing and branching, growing and branching, rooted in the past, stretching toward the future.

We know . . . what Seamus Heaney knew . . . what drove his pen to write . . . It’s what Mimi said to me not long ago as we watched Craig and Patti play ping pong. I asked her “What’s the one thing your mom taught you that you would want to pass on?” I was fishing for something trivial, maybe a recipe, or a bit of family lore. Mimi was having none of that. Without missing a beat, she said,

“Family is everything.”

In this world turned on end, the only thing that matters is family. All else is a distraction.

Coco and Daddo are coming home. We’ve got a few more stops before we do. A few more sights to see. A few more Irishmen to meet. A bridge to cross. Some whiskey to drink. But, we’re coming home.

We’ve still got a family to raise.